There is now a huge amount of evidence from different countries and across different professional groups that being involved in a patient safety incident, particularly one where the patient is seriously harmed or dies can be very distressing1. The feelings of guilt, shame, incompetence, anxiety that are reported to be experienced by the healthcare staff involved in these situations are heightened when the individual perceives it was possibly something they did or did not do which caused the patient safety incident. Of the 1,463 doctors we surveyed in the UK2, 76% believed the experience of a patient safety incident affected them personally or professionally. 74% reported stress, 68% anxiety, 60% sleep disturbance and 63% lower professional confidence. Moreover, 81% became anxious that they might doing something again in the future which could lead to another patient safety incident.

Why support second victims?

It is not only doctors who experience physiological distress after involvement in an incident. In another study3 we found nurses showed higher levels of distress following a patient safety incident than doctors. For many, the emotional impact of being involved in an incident is short-lived, but for other individuals the effects are long-lasting. In our sample, 8% of doctors reported symptoms associated with post-traumatic stress disorder. This impact on the healthcare employees is the reason the term ‘second victim’ was coined. The emotional impact of being involved when something goes wrong are many, but there are other impacts too which make it so very important that employers, managers and colleagues don’t disregard, ignore, or even punish further the individuals involved.

There is evidence that distress and further loss of confidence can often be exacerbated by the patient safety incident investigation process – and this can lead individuals to burnout, a state of hyper-vigilance and/or the practice of defensive medicine. Some ‘second victims’ may even choose to leave the profession, especially in the absence of timely and tailored support from those around them. From a moral standpoint, supporting people in distress is essential and this includes supporting healthcare employees involved in patient safety incidents. From a healthcare organisational perspective, there is a patient safety, a staff health and well-being, and financial imperative to do so.

Patient Safety Incident Response Framework

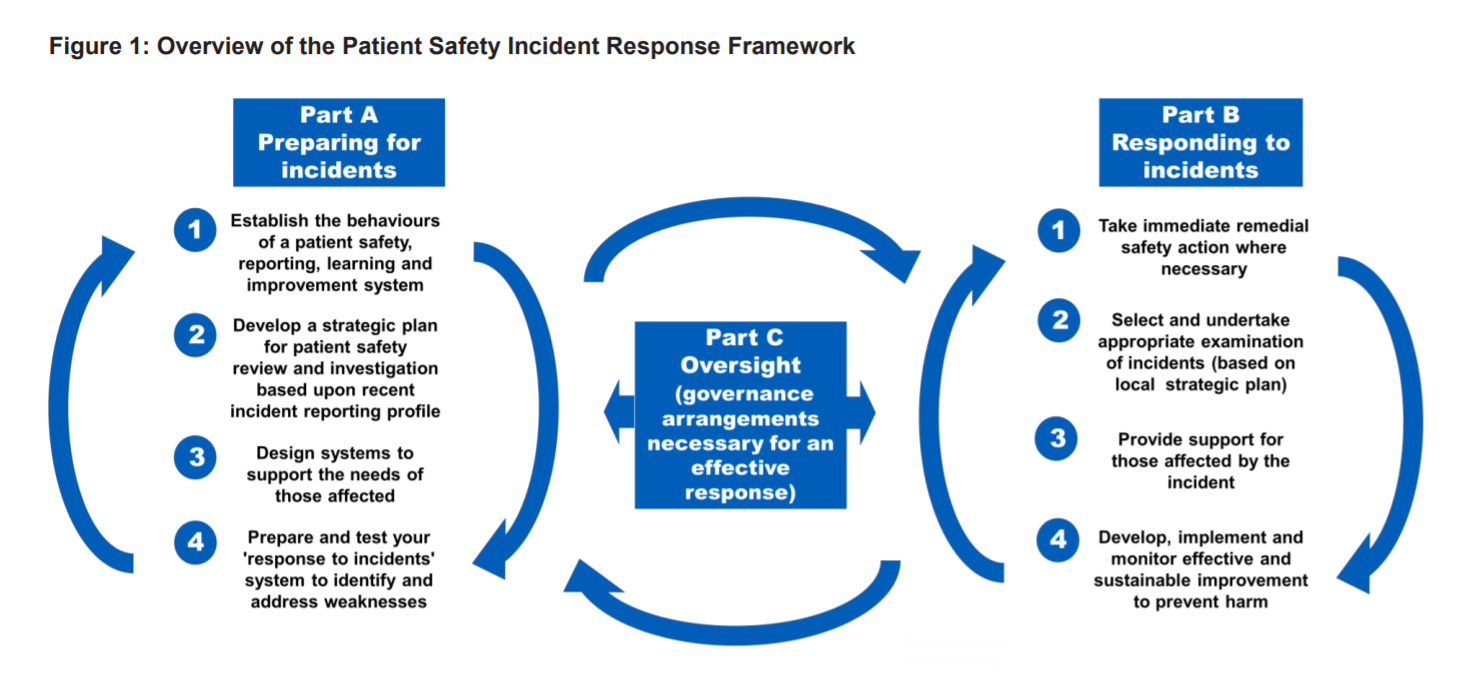

To support the NHS to further improve patient safety, NHS England and NHS Improvement are introducing a new Patient Safety Incident Response Framework4 (PSIRF). The PSIRF describes a new approach to patient safety incident management, one which facilitates inquisitive examination of a wider range of patient safety incidents “in the spirit of reflection and learning” rather than an approach which feeds into a “framework of accountability”.

Informed by feedback and drawing on good practice from healthcare and other sectors, it supports a systematic and compassionate response to patient safety incidents which is anchored in the principles of openness, fair accountability, learning and continuous improvement. The plan for the introductory version of the PSIRF is for implementation by nationally appointed early adopters during 2021.

The PSIRF outlines how providers should respond to patient safety incidents and how and when a patient safety investigation should be conducted. It clearly sets out how the needs of those affected by patient safety incidents – patients, families, carers and healthcare staff – are met.

Organisations must establish procedures to identify all staff who may have been affected by a patient safety incident and provide access to the support they need. A 2021 Healthcare Safety Investigation Branch national learning report5 further highlights the need for support systems for staff. Figure 2 in the report describes some of the approaches which may be offered before and/or after involvement in a patient safety incident.

Organisational staff support model (OSSM)

The Organisational Staff Support Model for patient safety incidents (PSI) below has been developed by the Yorkshire and Humber Patient Safety Translational Research Centre (YHPSTRC) and Yorkshire and Humber Improvement Academy (YHIA). Members of the YHIA’s ‘A Just Culture Network’ have contributed to the model.

We have based the Organisational Staff Support Model (OSSM) on Cooper and Cartwright1’s ‘Intervention Strategy for Workplace Stress’, which recommends that organisations adopt a “3-pronged” approach (primary, secondary, tertiary) to prevent and manage employee stress. Primary level interventions aim to reduce stressors that compromise employee wellbeing; Secondary level interventions focus on stress reduction; Tertiary level interventions focus on remedial support.

The OSSM targets the specific workplace stressor/hazard of being involved in a PSI in a healthcare organisation as a healthcare employee. We have reconceptualised Cooper and Cartwight’s original goals of intervening at Primary, Secondary and Tertiary levels to reflect this:

- Goals for Primary level intervention: to provide a proactive, supportive working environment to facilitate adaptive coping before/in the event of being involved in a PSI (e.g. just, learning culture/psychological safety, psychoeducation for better preparedness and collective understanding).

- Goals for Secondary level intervention: to provide rapid response after a patient safety incident, to promote coping, reduce severity or duration of stress and longer-term emotional difficulties.

- Goals for Tertiary level intervention: to identify and provide individualised support after a patient safety incident for those whoexperience severe, longer term emotional sequelae and/or whose ability to function is disturbed.

There are practical, ethical, moral and financial arguments for providing comprehensive staff support. Research consistently tells us that most healthcare professionals are involved in a PSI at some point in the career, and the risk can never be entirely eradicated within such a human system. The ‘Second Victim’ experience is associated with distress, compromised patient safety, absenteeism and turnover intentions2.

Adopting a comprehensive “3-pronged” approach has the potential to support staff with adaptive coping (and even thriving) after such incidents, and minimise long-term harm and poorer mental health outcomes associated with merely ‘surviving’ or ‘exiting’ the organisation3. It may also help foster a psychologically safe culture in which PSIs are more openly reported and learned from4.

References

- Cooper,C.L., Cartwright, S., (1997). Intervention Strategy for Workplace Stress

- Burlison, J. D., Quillivan, R. R., Scott, S. D., Johnson, S., & Hoffman, J. M. (2016). The effects of the second victim phenomenon on work-related outcomes: connecting self-reported caregiver distress to turnover intentions and absenteeism. Journal of patient safety.

- Scott SD, Hirschinger LE, Cox KR, McCoig M, Brandt J, Hall LW (2009) The natural history of recovery for the healthcare provider “second victim” after adverse patient events. Qual Saf Health Care, 18 (5): 325-330

- Joesten, L., Cipparrone, N., Okuno-Jones, S., & DuBose, E. R. (2015). Assessing the perceived level of institutional support for the second victim after a patient safety event. Journal of patient safety, 11(2), 73-78.

To identify and provide individualised support to staff who experience severe and/or longer-term emotional sequelae and/or disturbed ability to function after a patient safety incident.

Tertiary support may involve ↓ click to scroll down

To provide rapid and appropriate responses to support staff in the aftermath of a patient safety incident, to help reduce the severity or duration of stress experienced and prevent longer term emotional sequelae.

Secondary support may involve ↓ click to scroll down

To provide a supportive working environment which facilitates adaptive coping in the event of staff being involved in a patient safety incident.

Primary support may involve ↓ click to scroll down

Adapted from Cooper, C.L. and Cartwright, S. (1997) An intervention strategy for workplace stress. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, Vol. 43(1), 7-16.

For more information on the OSSM and how it might be used to inform improvements in the support systems available for healthcare staff involved in a PSI in your organisation, please contact Academy@yhia.nhs.uk. The OSSM© is copyright of Bradford Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, 2021. This material must not be reproduced or shared without the permission of the Improvement Academy.

Primary support may involve

Role modelling a compassionate and psychologically safe culture

Place importance on relationships, connectedness, civility & kindness:

- Individuals and teams encouraged to build non-hierarchical connections based on shared experiences of service/role

- Investigation/Risk Team builds relationships & trust with staff via visibility, friendly communications, sharing learning & showing humanity and support

- Use NHS Staff Survey & Pulse Surveys to inform action

Provide symbols of caring and deliver consistent messages “it’s ok to not be ok”:

- Quiet areas, wobble rooms, Health and Wellbeing Hubs

- Emphasise importance of regular breaks, annual leave, and support flexible working

- Regular Schwartz Rounds*

- Visibility of and access to peer support and clinical psychology teams

- Support, reassurance and normalisation of “it’s ok to not be ok” – role modelled through all levels of the organisation including Senior Leaders

- Freedom to Speak up Guardians

Fair, transparent, learning-focused investigations/reviews

- A clear strategy exists for supporting staff involved in a patient safety incident (PSI)

- Staff know what to expect should they be involved in a PSI e.g. individuals are not stigmatised, penalties (financial, reputational, disciplinary) are avoided

- Procedures are in place to actively support staff to disclose an incident to the patient & family

- The investigation process is clearly documented and easily accessible

- Staff perspectives of the incident are sought and considered integral to learning

- Feedback is sought from staff on their experiences of being involved in a PSI and used to continuously improve support for staff to optimise staff wellbeing outcomes

Educating staff on the impact of Patient Safety Incidents (PSIs)

For staff working directly with patients and their families/carers:

- Generalised resilience training*

- Targeted resilience training* to help staff prepare psychologically for involvement in a PSI & aid coping and recovery

For PSI teams, HR teams, risk management teams, line managers:

- Sensitising training/awareness raising to understand: (i) ‘normal’ responses to PSIs & (ii) interpersonal treatment which supports, or further harms staff involved.

References

Schwartz Rounds:

There is currently no research evidence linking Schwartz rounds to the prevention or reduction of ‘second victim’ experience after patient safety incidents. However, findings from a recent, robust evaluation suggest they may be beneficial for staff before and after experiencing PSIs, with regard to supporting psychological safety, processing, relational connection and recovery/healing. Attendees report feeling an organizational culture shift, where emotional disclosure, empathy and compassion are normalized (psychological safety). They describe value in having time to think and reframe negative patient experiences, acceptance of experiences (processing), reduced negative assumptions about colleagues and increased compassion and empathy (relational connection). Increased emotional resilience is also reported by those attending Schwartz rounds, and they experience a 19% reduction in psychological distress in comparison to non-attendees (recovery/healing).

Resilience training:

A recent Cochrane review reported that resilience training for healthcare staff may improve resilience generally, reduce symptoms of depression and stress after an intervention ends – although they do not seem to reduce anxiety or improve wellbeing. However, new evidence is emerging that healthcare professionals may be helped to psychologically prepare (e.g. through CBT or ACT) for involvement in adverse events, to promote adaptive coping and minimise the degree of harm suffered.

Secondary support may involve

Support from line manager

- Recognition of potential impact of the PSI for individuals and the team

- Clear information about the investigation process

- Support throughout the investigation e.g. for Duty of Candour, regular check-ins

- Immediate actions for staff/the team where indicated e.g. immediate release or time off work where appropriate. This needs to be managed sensitively to avoid perceptions of ‘suspension’

Support from others, including rapid response teams, to process the incident

- Peer support systems* accessed on a self-selected basis

- Mental Health First Aider

- Post-incident debriefing* (peer- or psychological therapist-led) e.g. Critical Incident Stress Debriefing

Information and guidance (signposting or self-directed access)

- Second Victim Support website

- Staff support and advocacy groups

- Professional body advice lines

- Professional steward or Trade Union representative

References

Peer support systems:

A consistent finding in the literature is that staff mostly want the support of peers after adverse events, including PSIs. Through shared experiences and immediacy, peer-based support can help to normalise the complex feelings experienced after an incident.

Post-incident debriefing:

In healthcare, team debriefs are frequently used to learn from clinical events, drawing upon approaches such as REFLECT (Review the event, Encourage team participation, Focused feedback, Listen to each other, Emphasise key points, Communicate clearly, Transform the future). ‘Psychological debriefing’(PD) or ‘Critical Incident Stress Debriefing’ (CISD) is a different approach, facilitated by two trained debriefers/psychologists, between 48 and 72 hours after the incident. PD/CISD emerged in the 1980s, designed as a group intervention for emergency services personnel exposed to potentially traumatic events; occupational hazards inherent in their job. In this sense, CISD/PD is an occupational health tool of community support and cohesion, rather than a ‘treatment’ to prevent or treat PTSD (Richins et al., 2020): “CISD employs the active mechanisms of early intervention, verbal expression, cathartic ventilation, group support, health education, and assessment for follow-up” (Everly, Flannery & Eyler, 2002, p.173).

The use of PD/CISD on a one-to-one, personal basis and/or as an intervention to prevent or treat PTSD is contraindicated: a Cochrane Review (Rose et al., 2002; updated 2010) found no evidence for the effectiveness of individual-participant, single-session debriefing in preventing PTSD after traumatic incidents, and found some suggestion that it may increase the risk of depression and PTSD. NICE (2018) recommend that psychologically focused debriefing is not offered for the prevention or treatment of PTSD.

However, when used as part of a comprehensive program of organisational support, incorporated into working practice and conducted appropriately by trained facilitators to evidence-based criteria, PD/CISD has been reported to be an effective tool (Everly, Flannery, & Eyler, 2002; Richins et al., 2020):

- CISD/PD receives positive feedback from participants: e.g. according to UK scoping review of 50 studies, emergency responder employees consistently express satisfaction and appreciation from being able to discuss their experiences (Richins et al., 2020).

- PD/CISD appears to support natural coping processes and may reduce problematic coping behaviours: when peer group processes are mobilised through CISD/PD, natural recovery without additional intervention (e.g. occupational health) is found to be more likely (Richins et al., 2020). In a randomised controlled trial, firefighters’ participation in CISD was associated with significantly less alcohol use and greater quality of life post-intervention – although there was no significant effect on post-traumatic stress or psychological distress (Tuckey & Scott, 2014).

Three necessary conditions have been identified for effective early interventions (including CIDS/PD): (1) they are supported by senior leadership teams; (2) they are attuned to unique organisational cultures; (3) they draw upon existing peer support systems and social cohesion in teams (Richins et al., 2020, p.8).

NICE (2018a). Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder: Evidence Reviews For Psychological.

Richins, M. T., Gauntlett, L., Tehrani, N., Hesketh, I., Weston, D., Carter, H., & Amlôt, R. (2020). Early post-trauma interventions in organizations: a scoping review. Frontiers in psychology, 1176.

Tamrakar, T., Murphy, J., & Elklit, A. (2019). Was Psychological Debriefing Dismissed Too Quickly?. Crisis, Stress, and Human Resilience: An International Journal, 1(3), 146-155.

Tertiary support may involve

Support to fulfil role

- Adjustment of duties

- Mentoring to rebuild confidence in carrying out tasks after the PSI

- Flexible working arrangements

- Possible leave of absence (not appropriate for everyone and requires careful handling, e.g. may feel like ‘suspension’)

Continuous support to aid recovery

- Planned check-ins with line manager

- Personalised crisis & support planning (e.g. if evidence of suicidal ideation)

- Sustained access to team/peer support*

- Space and time for reflection and rediscovery*

Recognition of the the need for enhanced mental health support and enable access to (where appropriate)

Holistic/spiritual approaches:

- Discuss support from faith leaders e.g. chaplaincy

- Meditation, mindfulness

- Voluntary sector providers (e.g. MIND, Samaritans)

Psychological therapies:

- Counselling or specific trauma-focused therapy e.g. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy*, EMDR* accessed via:

- Occupational health

- Regional Health and Wellbeing Hubs

- Royal Colleges and/or professional bodies

Where there is significant concern about mental well-being, support access to specialist mental health services, via:

- Mental Health First Aider

- Occupational health

- GP

- Crisis services e,g, 24/24 crisis lines

Opportunities to gain and share wisdom from the event

- Contribute to and implement recommendations or changes after an investigation

- Lead an improvement project/campaign

- Contribute to a Schwartz Round*

- Become a peer supporter

References

Peer support systems:

A consistent finding in the literature is that staff mostly want the support of peers after adverse events, including PSIs. Through shared experiences and immediacy, peer-based support can help to normalise the complex feelings experienced after an incident.

Space and time for reflection and rediscovery:

There is no high quality evidence for the effectiveness of having space and time for reflection and recovery after PSIs. However, through our extensive research into the impact of adverse events across the past decade, healthcare staff sharing their experiences consistently underline the value of reflecting on, processing and learning from the incident with trusted colleagues and senior supportive mentors. Furthermore, there is evidence from Schwartz rounds that healthcare staff value time to process, share and gain new perspectives on difficult workplace incidents.

Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR):

Numerous RCTs and meta-analyses have demonstrated effectiveness of EMDR therapy in treating Post-traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and associated depression, anxiety and distress. After being involved in a PSI, healthcare staff may experience PTSD or similar symptoms, such as intrusive thoughts, flashbacks, hypervigilance, depression and shattered assumptions about themselves and the world. Therefore, EMDR for healthcare staff experiencing this type of distress may be beneficial. However, currently, there does not seem to be any evidence for EMDR’s effectiveness with healthcare staff for PSI-related trauma. We therefore recommend its use on a case-by-case basis, according to the individual’s symptoms and difficulties.

Acceptance and commitment therapy:

A recent systematic review and meta-analysis found that ACT interventions for Healthcare professionals are effective in improving both general and work-related distress. Less evidence is available for using ACT interventions to specifically target distress triggered as result of involvement in adverse events/PSIs. However, there is some evidence that ACT may be beneficial for people experiencing shame, self-criticism and lack of self-compassion – feeling/cognitions which are prevalent after PSIs.

Schwartz Round:

Recent qualitative research reported healthcare staff spoke positively about sharing their stories of being involved in a PSI in Schwartz Rounds. Those interviewed reported increased emotional resilience and greater empathy from others. The more visible emotional disclosure of their experiences facilitated trust, tolerance and compassion helping change culture.

Notes on references

Given the limited number of systematic reviews and other high-quality research describing the effectiveness of interventions to support staff involved in patient safety incidents in healthcare, the approaches/interventions described in the support levels above reflect the best available evidence which may include research undertaken outside of healthcare.

The approaches/interventions marked with an asterisk (*) are those which have the strongest evidence base or are those which must be interpreted with care if being used to develop and implement interventions to support healthcare staff involved in a PSI. A brief summary of the research for each level of support is included.